I find myself with a few spare hours to spend writing—at last!—on this lovely holiday morning. It's an unexpected white Christmas here in beautiful, scenic Omaha, with a steady snowfall and a rapid accumulation on the ground. I say "unexpected," because yesterday was a Christmas Eve so warm that I was more comfortable outside in short sleeves than a jacket, and that entirely in spite of the fact that it rained all day. Family get-togethers aren't happening until the evening, and as a bona fide Baldur's Gate 3 widower, my wife is contentedly occupied with her druid character and something-something, goblin camp, Astarion. (I can't be arsed to pay that much attention to modern AAA video games.) So, at long last, I can write.

There is a myth that persists in grognard circles that AD&D is something akin to "OD&D plus all of Gary Gygax's personal house rules." This follows from the notion that white box 3LBB OD&D is a kind of "toolkit" for making your own game, a starting-point from which every referee will begin. As each campaign develops, and referees add house rules to suit their particular needs and preferences, every OD&D table diverges, each one becoming something unique, something bespoke to that referee. OD&D is the foundation; from it, every referee builds their own fantasy campaign, their own D&D. This tendency toward variation, however, makes cross-campaign compatibility functionally impossible, hence the eventual declaration from on high that OD&D is a "non-game." In its place, the universally-accepted "standard" ought to be AD&D, because while AD&D is only one possible pathway, one possible game that could be derived from OD&D, it's the path taken by D&D's more prominent, more involved, more mechanically-minded designer. It's the intended path, the trail blazed by the referee with more D&D experience than anyone else could possibly have.

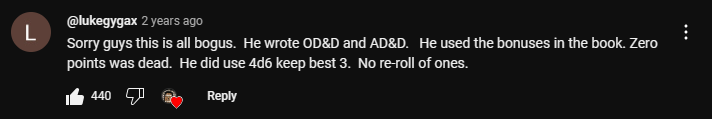

Now, this is not the most pernicious myth surrounding Gygax, OD&D, and AD&D. No, that award must doubtlessly go to the myth of "Gary's secret house rules," which is the now roundly debunked idea that a certain set of house rules used for one game of OD&D one time maybe was "the way Gary played." Even though it isn't true—

—the legend persists that "AD&D is full of rules that nobody used, not even Gary Gygax." That most of AD&D, in other words, is useless padding: unnecessary rules-bloat at best and untested garbage at worst.

Why do I bring up this second, rather more insidious myth? Because it's in direct tension with the first one, and I think that it illustrates something useful. We can call these two myths the myth of "precedent" and the myth of "padding": the first asserts that AD&D's complexities are organic and arose through play, while the second implies that they exist only to inflate the page-counts of rulebooks and thereby distinguish AD&D as a different game from OD&D (ostensibly motivated by a cynical agenda to screw Dave Arneson out of royalties).

Both myths serve different aims. The "precedent" myth is excellent at justifying a "Gygaxian" view of OD&D and AD&D. By "Gygaxian," I mean a certain picture of the history of the game that paints Gary Gygax as the chief architect of OD&D; AD&D 1st edition as a collated refinement of OD&D writ large (the disorganized sprawl of booklets, supplements, newsletters, and fanzines); and the later game that AD&D 1st edition was becoming as it moved in the direction of Unearthed Arcana and the Gygaxian 2nd edition that we never got as the pinnacle of the game's evolution. This is the corner of the hobby that treats AD&D as the one true game; 3LBB OD&D as the zeroth edition, the unfinished prototype of the game; and everything that came later as devolutions to be blamed on Zeb Cook—not just 2nd edition, but also everything BXc. (This is, of course, a broad caricature of several different points of view on the matter; but that's okay. At this point, I'm still just laying out the ideological landscape. The point is, this "camp" is where you find everything from "by-the-book, tournament AD&D"; to the Knights & Knaves Alehouse's narrow conception of "Gygaxian" D&D; to the so-called "BroSR"; to the nostalgic gamer who "comes home" to just running AD&D rules-as-written, and the accompanying disparagement of house rules as an inevitable dead end or waste of time.)

The "padding" myth, meanwhile, has been prominent in the OSR ever since the late 2000s: it's one of the foundational myths of the OSR, for it serves to justify the "DIY," toolkit approach to OD&D. It exhorts referees to make the game their own, to tinker, to house-rule, to create retro-clones and heartbreakers. It pines for a lost age that never was: for a timeline where AD&D never happened, never dominated the hobby, never contributed to the rules-heavy, charts-and-tables aesthetic of 80s RPGs; where not only did game-rules stay lightish and freewheeling and firmly in the hands of free Kriegsspiel minded referees, but maybe even the Hickman revolution never happened, and the sandboxes and open-ended scenarios were never displaced by railroads and performative thespianism.

Both of the myths I've just described are cartoonish exaggerations. No individuals that I'm aware of actually hew to either view without nuance. And, of course, reality is complicated. History is complicated. And while I have lampooned two opposing points of view, I am also strongly sympathetic to both. I can see where the Gygaxian, rules-as-written, by-the-book AD&D players are coming from. I can see where the DIY, toolkit, tinkering OD&D players are coming from. And while I am personally more in agreement the latter view of the game, I recognize equally the ahistoricity of its myths. These are constructs: arbitrary and in service to an agenda.

The "precedent" myth is complicated by the fact that much of AD&D didn't come from Gary Gygax's home campaigns. We know that other designers contributed to the rules. We know that many of the rules were collected from outside sources. And yet, the "padding" myth doesn't hold water either, because very little of AD&D's supposed "bloat" isn't useful. None of it is what I would call "garbage" design. Heavy in places, yes, but certainly not everywhere. A lot of the crunch is very clearly organic, in that it must have arisen from a need that came about in play. I'll cite two brief examples, and I think they'll serve to illustrate my own view on AD&D.

Many of us have read the DMG (1979) cover to cover. But it's also true, I think, that even those of us who have done so tend to be more familiar with the earlier pages nearer to the beginning of the book. That's natural: that's just what happens when the aborted attempts outnumber the read-throughs that don't just get started but also get finished. And pretty much everyone who has attempted to read through the DMG is familiar with the early section on spying and assassination missions. This section is an oft-cited example of AD&D's "useless" cruft, mechanics that bloat the system without having any real value. I've heard this charge leveled from all quarters, and every time, it baffles and astonishes me. Have these people never played a game of D&D that wasn't strictly the player character adventurers always doing their own dirty work? Have they never played a game that got above name-level and put a PC in charge of a stronghold, a fiefdom, or any kind of organization? Any game where the player characters have the ability to send agents to do work for them "off-screen," so to speak, because that sort of thing is both plausible and sensible? I submit that a game where the players have sufficient agency to make these sorts of moves will categorically benefit from having clear rules governing the time required and the odds of success for spies or assassins. These rules are so very clearly the result of necessity and campaign play. And yet the basic game has no equivalent, no robust framework beyond the "Spy" entry in the section on NPC specialists in the Expert Set or the Rules Cyclopedia, which says simply "the DM decides" and then offers no suggestions for how to decide. For my part, I can say with some confidence that whenever a player character decides to hire out a spy to carry out a mission, I'm going to consult the DMG to decide how it goes.

But just because I'm inclined to pull that one rule out of AD&D and apply it to my own OD&D games, that doesn't mean by any stretch that I'm actually running AD&D. And the reason why has to do with the overall ratio of rules that I find personally useful versus rules I'd prefer to ignore. A great example of the latter comes from the DMG's rules for training to go up an experience level. Now, I'm of the opinion that training between experience levels is absolutely vital to a well-run D&D campaign, because it creates gaps during which characters become temporarily indisposed and unplayable, forcing players to expand their personal roster of PCs. But it's the time rather than the cost which makes this mechanic effective. I think that the cost in g.p. required to train, at least at low levels, is too inflated in AD&D, too much bent in the direction of siphoning cash out of the PCs' coffers so as to keep them artificially poor and treasure-hungry. (I'm of the opinion that PCs need very much to be saving up that treasure, or putting it to use on personal projects like strongholds, research, crafting, and the like.) Moreover, I have absolutely no use for the E/S/F/P grading system. While I fully understand that this mechanic exists to deliberately incentivize a certain approach to play that prioritizes playing to alignment and class archetypes, I do not happen to value that approach overmuch. I don't believe that alignment needs to be involved in micromanaging player character behavior, and I certainly don't believe that playing a character class to the stereotypical hilt merits reward or reinforcement. I get why these mechanics are there; I respect what they're for and the fact that they work; and I reject them at my game-table for my own considered reasons.

If we set aside all of the rules that OD&D and AD&D share and only consider the areas where they differ, on balance, I reject more of AD&D's extra rules than I keep. And, lest we forget, OD&D has some rules that AD&D does not, and on balance I keep more of those than I discard. It's really just that simple: when you get right down to it, they're different enough as games and game systems that just picking one is the best place to start, and I've picked OD&D. Its mechanics suit me better; it's the game that I started with, so it more readily tickles the nostalgia bone; and its aesthetic is just different enough from the game's mainstream lineage (the Gygaxian path which can be traced from "0e" through AD&D to the d20 System™ editions) that it has an identity of its own. Those latter two points aren't to be scoffed at, either: nostalgia matters, and aesthetic matters, and I dearly love the Mentzer–Elmore–Allston–Dykstra aesthetic (which I'm going to summarize as "Mentzerian") of 80s red box and 90s black box OD&D.

With respect to OD&D, I am a tinkerer. I take the version that I like best (BXc.), I add bits and pieces from other versions that I like (including Holmes, 3LBB, AD&D, and retro-clones), and I add my own house rules and innovations. There is a solid foundation that comes from published rules-as-written, but my game is bespoke to me, suited to my needs and preferences. With respect to AD&D, I treat it as precedent, but nonbinding precedent. It is a body of case law, but the kind that you consult to inform your understanding of statutory law and thereby aid your rulings, not the kind that makes up a body of common law. I do not play AD&D, because I do not need all of AD&D. (Which is not to say that I don't respect AD&D for what it is; nor do I assume that if someone prefers AD&D, that means that they "need" more rules, or that needing or preferring more rules is at all a bad thing. Far from it.) Whereas I play OD&D because I do have need of something more robust than an ultralight.

(Secondarily, I have a keen interest in playing D&D games set in milieux other than high fantasy sword & sorcery. While AD&D's Historical Reference line is an admirable attempt at setting D&D games in various ancient, medieval, and early modern periods, those seven wonderful green-cover splatbooks nevertheless pale in comparison to the vast offering of OD&D-compatible OSR games that run the gamut from space opera to four-color superheroes. If there is a second major reason to choose OD&D over AD&D, it is this flexibility. The OSR has, against all odds and common sense, somehow managed to expand OD&D into a functionally "universal" TTRPG system.)

I've already passed through my "ultralight" phase, where I wanted to give up D&D and play something like Risus instead. I came out of it when I discovered that ultralights are a poor tool for full campaigns, and a poor tool for old-school games, being better suited to trad-style play. This is, perhaps, why I have such visceral distaste for the "artpunk" and "NSR" subcultures (and why the "FKR" approach seems to me so misguided and uninteresting). When the rules are too light, they better serve a puppet-master GM (the sort of dice-fudging, plotline-writing GM that in the past I've called a "Maestro Houdini") than they do an impartial worldbuilder–referee. ■

Bro!

ReplyDeleteBro?

DeleteIt's interesting to compare your reasoning to JB's recent posts on why AD&D does it for him. He has a very different conclusion, but similar reasoning. Play what works best for you, to world-build your campaign.

ReplyDeleteI'm very much in your camp. BECMI is my base, but I take what I like and need from other editions to suit the game I want to run.

To be sure, JB's recent turn to AD&D is one of the factors that prompted me to ponder and clarify my thoughts on the matter.

DeleteThe other factors are my own nostalgia for the game (since I played more AD&D than OD&D as a kid), and my own flirtations with it in recent years: running the occasional one-shot, playing around with AD&D house-rules, mixing OD&D and AD&D in various ways.

It's a truism among grognards that everyone mixed BX(CMI) and AD&D when they were kids, but my friends and I never did that. We always toed the TSR line and treated them as separate games. Doubtless, that still colors my perception of the game(s) to this day.