Welcome to the third post wherein I lay the groundwork for this blog's future direction. Today, I want to discuss the concept of play-style as it pertains to TTRPGs. In brief, play-style is an approach to playing RPGs, a set of norms and values and goals that pertain not just to how players play and referees run, but why.

Taxonomies of play-style are numerous; my favorite is The Retired Adventurer's "Six Cultures of Play." I do recommend following the link; it's practically required reading. While the Six Cultures taxonomy has as many detractors as advocates—probably more of the former now that some time has passed since it first appeared—I nevertheless find it valuable, because it matches up very well with my experience and understanding of the wider hobby, both in real life and online. I prefer to use the term "play-style" over culture, though, because even though the latter is accurate enough (cultures most certainly involve the continuous transmission of norms and values), it implies that a "culture of play" is something bound to individuals or gaming groups, something passed on from GM to GM like a tradition or an inheritance. "Play-style" makes it clearer that a given group can play different games in different styles, though it does come with its own pitfall, namely the overly-close association of specific game systems with play-styles. The truth of the matter is, even the same game system employed by the same gaming group can be played in a variety of styles.

It's about how you play, and why.

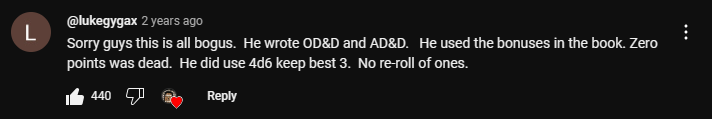

The "what you play" matters less than the how and the why. This is the infamous "System Matters" debate, the contentious notion that the rules of an RPG are determinative; and the equally contentious corollary that if a GM momentarily sets aside a rule because it conflicts with the desired play-style, that's tantamount to no longer playing that game ("as intended" being the oft-unspoken coda clipped off the end of that statement). This is a subject that will certainly require its own full post; for now, suffice it to say, I think that this sort of determinism and slavish adherence to "designer intent" is usually bogus, but not wholly vacuous. Designer intent is a thing, and System Does Matter, just not nearly as much as the Forge forums' indie designers liked to imagine.

So, getting back to the Six Cultures. I've said that they match up pretty well with my experience. The only perspective I can really add here—and this will reverberate through future posts when I need to bring up the concept of play-style in other discussions—is that I don't think clean divisions can be made between some of them. And The Retired Adventurer (henceforth "TRA") says as much, acknowledging that the Six Cultures have fuzzy, porous boundaries; that's fine, that's expected, but it's not what I mean. I mean that I find it more helpful to think of Three Style Families than Six Cultures. TRA draws some clear distinctions between Classic and OSR, and between Trad and OC/Neo-Trad; I think that the distinctions are overstated. (Heh; there I go, being more of a lumper than a splitter yet again. Thank goodness I never majored in cladistics.)

I think of TTRPG play-styles as falling into three overarching categories: Old-School, Traditional, and Avant-Garde. More specific styles are hierarchically nested within these broad families, whether by shared history or shared values and goals.

Old-School is the mode of play closest to wargaming, original to D&D as it was designed by Gygax, Arneson, &al., and revived (unevenly and with different emphases) by the OSR. While there are certainly noteworthy differences between Old-School play as it existed in the 70s and as it exists now, these are a matter of emphasis and principle. In the 70s, without clear contrast between itself and other play-styles, Old-School play was necessarily less defined and more amorphous, more all-encompassing of the hobby as a whole in a time before other styles could define themselves by splitting away from what the Lake Geneva and Twin Cities groups were doing. (And split off they did, and rapidly, as documented by Jon Peterson in Playing at the World and The Elusive Shift.)

In early Old-School play (TRA's "Classic"), more fudging and manipulation on the part of the DM would be regarded as acceptable or even laudable, for example, so long as such were aimed and keeping the game fair and challenging; whereas the modern OSR puts more emphasis on fair play through principled refereeing, avoiding techniques like fudging and illusionism. Another distinction, much more impactful IMO, is the OSR's continued tendency to focus on specific points of contrast between Old-School and modern styles—referee rulings, player skill, XP for treasure, lethality, consequences, &c.—at the cost of sometimes not seeing the big picture of campaign structure. While some elements of old-school games, such as open tables and "West Marches" style adventuring that begins and ends in town, have been emphasized, other elements, such as character rosters (also called "stables" or "troupes") and 1:1 time (including the widespread misconstrual of the vaunted "STRICT TIME RECORDS" as referring to dungeon turns rather than campaign days), have often gone ignored except in a few quarters. But the differences between early and present-day Old-School are nevertheless overwhelmed by the similarities they share, chiefly in terms of that they do emphasize in common: player agency, exploration of an open world, a broadly impartial referee, gameplay focused on challenge (though at times the OSR emphasizes verisimilitude to the utter exclusion of fairness), and perhaps less emphasis than many modern gamers are used to on characterization and thespianism.

Traditional (or "Trad") is the play-style which, ironically enough, most closely resembles narrative, interactive media—not just RPG video games, but practically all modern AAA video games, with their cinematic cutscenes and "RPG elements" (which, in the world of video games, just means character advancement or customization mechanics). The point of a Trad-style game is to have a cohesive story with a satisfying beginning, middle, and end, but one that the player characters were the "stars" of—without sacrificing strategic or especially tactical gameplay. The player characters "play through" the story, with their decisions introducing branches into how the narrative unfolds. This should seem very familiar to just about anyone who has ever been exposed to either tabletop RPGs or modern video games, because it is the dominant, mainstream way that interactive narratives are experienced in both media. This has been true of TTRPGs since at least the early-to-mid 80s, and it remains so right up through to the present day. Critical Role and Dimension 20 are as Trad as Trad can be.

Order of the Stick is a webcomic that tells the story of a "3.5e" campaign from an in-universe perspective, and you can tell just from reading through the comic that the campaign (though we never get any inkling of what the players or the DM are like) is just so very Trad, including a convoluted end-of-the-world main plotline and a swaggering "BBEG" (i.e., "Big Bad Evil Guy") in the character of Xykon the Lich, who, just like Sephiroth or Kefka or Exdeath or Golbez or Garland or Darksol or—man, JRPGs always have one of these, don't they?—serves as the story's main villain, but who will likely be supplanted by a true "final boss" in the climactic conclusion of the whole grand arc. That right there? That's super Trad.

The only thing that really distinguishes between old Trad and Neo-Trad is how essential the specific characters are to the plot. Trad is GM-driven: the GM has a story to tell, the player characters get slotted into that story as protagonists, and while the players' decisions can affect the outcomes, who the characters are doesn't matter so much. Different characters could be slotted into their place, and the GM's story would still unfold largely as planned. Neo-Trad is character-driven: like a prestige drama TV show, the characters' backstories and personal arcs of development are essential to the main plot. Change out the characters, and you have an entirely different story. Naturally, Neo-Trad play goes hand-in-hand with TTRPGs where the game mechanics themselves put a lot of emphasis on character customization: it is a matter of ludonarrative consonance to expect that characters who are central to the game's plot are also central to its mechanics. In Trad-style play, customizing your character—creating or building rather than merely generating—is how you declare from word one that your character is a protagonist.

Avant-Garde is the indie RPG sphere, especially the part descended from the Forge. It is concerned with rectifying some of the problems inherent in Trad play, such as the necessity to negate player choices or set aside game rules in order to effect narratively satisfying outcomes. (There is an inherent tension between games and simulations on the one hand, and coherent stories on the other. In a game or a simulation, unless the initial conditions have been very carefully circumscribed, practically anything can happen. There are no guaranteed outcomes. But that's bad for stories. In a narrative, you can't let just anything happen, because most of the time, most possible outcomes won't be good stories. Stories that meander, go nowhere, suddenly deflate the stakes, or seem to build up to something only to end without payoff, aren't satisfying stories. They can make for great parody or subversion at times, but only occasionally.) Consequently, the Avant-Garde play-style shares one major goal with the Trad style—to tell satisfying stories about themes and characters—but it wants to go about that by taking the burden of making a story happen off of the shoulders of the GM and placing it squarely on the game-mechanics, using rules to ensure that a meaningful story will emerge from play.

It is impossible to discuss this play-style further without at least mentioning the "GNS theory" of RPG "creative agendas," the invention of Ron Edwards, founder of the indie RPG design forums known as the Forge. The theory is considered discredited today, because it placed a great deal of emphasis on the notion of "coherence" in game design, which was the idea that a well-designed game aims at delivering on one and only one specific, designer-intended experience, which must be in service to only one of three possible creative agendas, those being Gamism, Narrativism, and Simulationism. Games that try to serve more than one master, so to speak, are unavoidably "incoherent" according to this theory, since there's inherent tension between the agendas. Now, entirely aside from the fact that "coherence" in game-design is something of a bullshit idea (because most groups of players would prefer to get more than one thing out of any one TTRPG), GNS is frustrating because its language is deliberately obfuscatory. People look at the word "Narrativism" and think, "oh, that means RPGs that are about telling specific kinds of stories," but, nope, that's Simulationism. Narrativism is chiefly concerned with forcing decisions on the player that, in the moment, define who the player character is, in order to drive conflict and produce a dramatic story out of that conflict. Simulationism? You'd think it means simulating an imaginary world, a believable world with a high degree of verisimilitude and accuracy to real-world outcomes—and along with that, crunchy game rules that look like actuarial tables or physics equations. But, nope, that level of predictability is part of Gamism. Simulationism is all about simulating specific genres of fiction and narrative tropes with game mechanics. (Experience points for treasure is, e.g., an example of a Simulationistic rule aimed at simulating a trope of sword & sorcery fiction.)

As you can see, it's a frustrating subject delve into. Edwards did that deliberately, to make us think about the language being used to describe our games, and boy did that ever backfire. Instead, everyone just took a surface-level look at the terms being used and then mixed up and misapplied what they were supposed to mean according to the theory. Good job, Ron. This is why the larger gaming community doesn't take GNS seriously anymore.

Now, I bring all this up to point out that one of the main strands in Avant-Garde play is storygaming, which takes coherence very seriously and sets Narrativism up on a pedestal as the best of the three creative agendas, the one that TTRPGs ought to be aiming at. Two of the key elements of the storygame play-style are (1) distributed authority over the fiction (meaning that players often have control over what exists in the world or what happens, aspects of gaming normally decided by the GM) and (2) an almost obsequious deference to the designer of a game as an auteur who intends for the players to experience something by playing that game rules-as-written, to the point where the designer's authority over the game is ideally supposed to trump that of the players or the GM (if there even is a GM)—as if the spectre of the designer were constantly hovering over the shoulders of everyone playing, to make sure that they're playing correctly—which is, I suppose, exactly what we should expect to see happen if we turn to rules systems to provide the consistently predictable outcomes required of satisfying stories.

While there are a huge number of indie RPGs designed with storygaming principles in mind, games like Burning Wheel and Sorcerer and Hillfolk, one of the first to achieve widespread popularity was FATE; but even FATE has been forgotten in the wake of Apocalypse World (and its descendant "Powered by the Apocalypse" games, including Blades in the Dark and its descendant "Forged in the Dark" games). But I do need to stress here once again that play-style is a way to play, not a kind of game. You can run OD&D in an Old-School way or a Trad way or even an Avant-Garde way if you want to. Play-style, creative agenda, and a third concept that I need to introduce next—"stance"—are all independent of system. A game system can facilitate or fight against any of these things, but they're mostly imposed on games by players and referees.

Stance is a concept vital to some of the other strands in Avant-Garde gaming, such as Nordic Larp and Israeli Tabletop, because those sub-styles often concern themselves with player emotions and states of mind. (When a player feels the emotion their character is feeling, that's called bleed; when a player feels like they're actually in the game-world or the story, that's immersion.) Stance is a term that also comes out of the Forge, and thankfully, it's much more straightforward and useful. It has to do with the relationship between the player and the character, how the player uses the character to make decisions and interact with the game world. Traditionally, there are four identifiable stances—Pawn Stance, Actor Stance, Author Stance, and Director Stance—but I don't think that list is exhaustive.

• Pawn Stance is treating the player character like a tool or game piece, an empty vessel into which the player self-inserts; the player makes decisions that look like smart, winning moves from the player's perspective—or decisions that come from the player's own drives, desires, motivations, and emotions. (Pawn Stance aligns well with Old-School play. It is also often dismissed as mere metagaming, "Mary Sueing," or "bad, one-dimensional roleplaying." But there's little room to deny that Pawn Stance can, at times, facilitate a great deal of bleed and immersion—because it minimizes the distance between player and character and maximizes the identification between the two.) (NB—Depending on how you look at it, it may be useful to distinguish between "true" Pawn Stance, which focuses on optimal moves and "winning" the game; and "Self Stance," which focuses on treating the player character as a player avatar. In effect, this would be drawing a distinction between an "out-of-character" and an "in-character" variety of this stance.)

• Actor Stance treats the character as a fleshed-out person with personality, psychology, motivation, &c. all distinct from the player. Players take an Actor Stance when they try to do what the character would do (and not necessarily what the player would do in the character's place). Crucially, it's less about outward, performative thespianism and more about the internal decision-making process. Basically, improvisational method-acting. (Trad play often puts Actor Stance upon a pedestal as the only kind of "real" roleplaying and dismisses everything else as either inferior metagaming or pretentious wankery.)

• Author Stance and Director Stance are similar in that they both envision the player "hovering over" the character (i.e., an explicitly "out-of-character" relationship between player and character), making decisions that drive the character to do things that aren't necessarily the smart move or "in-character," but rather things that generate the best story. In simplest terms, Author Stance is when the player makes the character do something that drives conflict, while Director Stance is when the player makes the character do something that generates emotion. Both are fundamentally about creating drama, and they're especially important to those lesser-known strands of Avant-Garde gaming that exist alongside storygaming (but they also have a strong presence in storygaming as well, especially in the more collaborative, "writers' room" sorts of games).

The most important thing to remember about stance is that it's fluid and nigh impossible to discern in someone else. Most players are constantly "code-switching" between stances from moment to moment as they play; and nobody other than the player can ever truly tell what stance they're taking with respect to their character at any given moment.

Okay; so now that I've outlined the concept of play-style as I understand it, I'll next time be doing a deep dive specifically into the Old-School play-style and the many, many gameplay elements that constitute it. This will be, fundamentally, a statement of the way that I run games—or, at least, the ideal that I want to strive for. ■